In 2013, snowy owls mysteriously began appearing in parts of the United States that don’t typically see them: Washington, D.C., Kentucky, Nebraska. It was the first signs of what scientists call an irruption, or rapid population boom in snowy owls. And this particular one would be the biggest irruption in 40 or 50 years.

Dave Brinker, a biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and his colleague Scott Weidensaul jumped at the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to turn this boom into data. They launched a research effort named Project Snowstorm, and crowd-funded enough money to purchase two dozen lightweight GPS transmitters custom-designed to fit on the backs of owls. Soon, streams of data came pouring in. The information shed light on the mysterious lives of these birds: hunting patterns, obstacles and dangers, and their migratory routes through Canada, the U.S. and the Arctic Circle.

In the few days I spent with the Project Snowstorm team, they trapped two owls on the chilly coast of Assateague Island, Md. before tagging and releasing them once more into the February wind.

The story was published on NPR.

The research team attaches a numbered band around the owl's foot which will identify her if she is ever recaptured.

A GPS transmitter is fitted with straps around the owl's back.

This owl, which was trapped off Assateague Island, Md., is given the name Hungerford by the research team.

The research team measure the owl's wingspan, tail length and fat stores.

Blood and feather samples help the team gather broad insights into the owls that are part of the irruption.

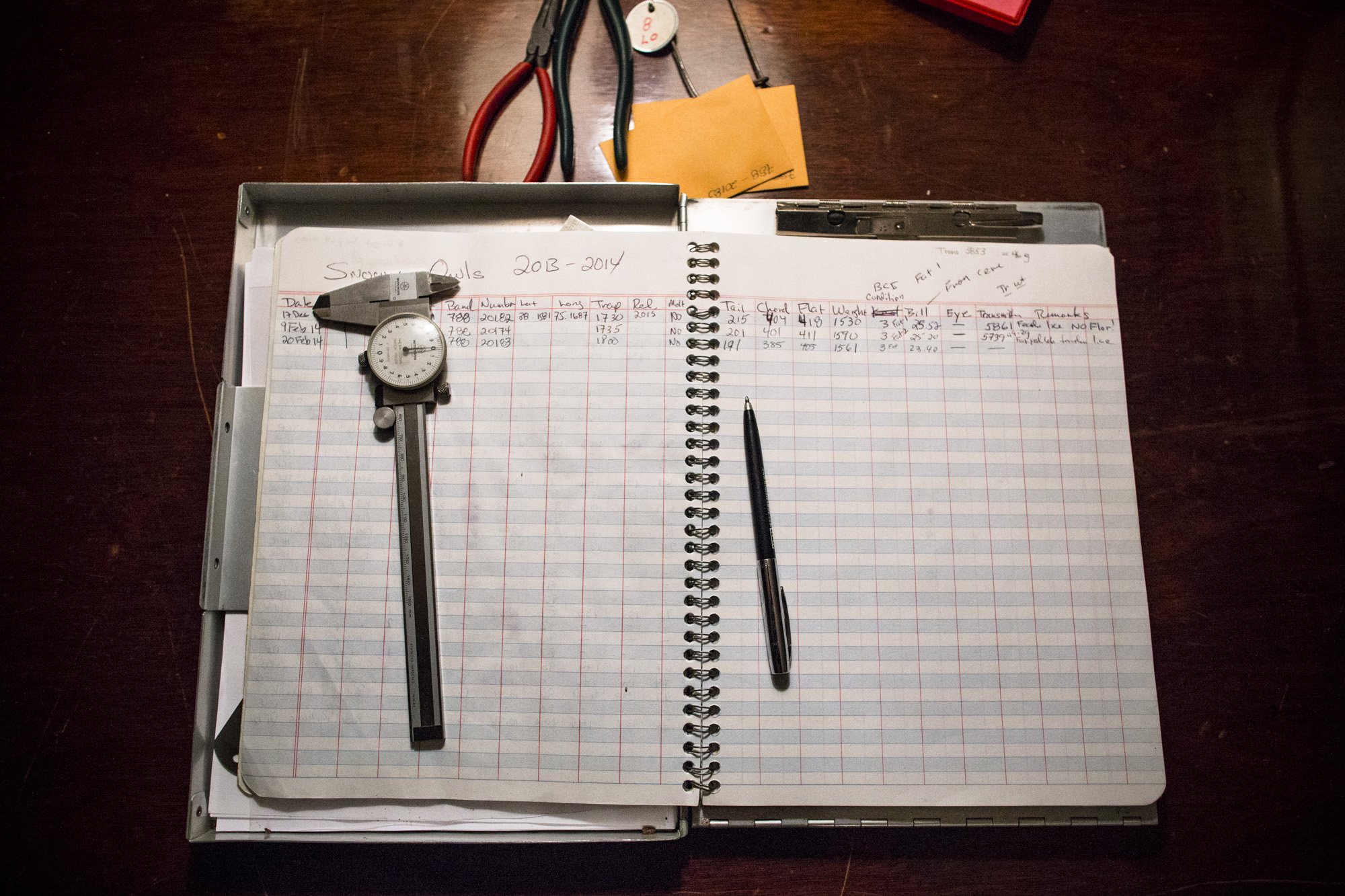

The research team's logbook keeps track of owl measurements.